December 2, 2021 Jermyn Street Theatre, London

Can you think of a Shakespeare play where a sea voyage is not accompanied by a tempest? Viola and Sebastian are shipwrecked in the opening scene of Twelfth Night as a result of a violent storm. Pericles suffers not one but two storms at sea, the second resulting in the death (we are led to believe) of his wife, Thaisa. Antonio (in The Merchant of Venice) loses his previous cargo when his merchant ship is destroyed in a storm, and nearly forfeits a pound of flesh (and his life) as a result. Even in Macbeth the Witches use the thumb of a shipwrecked sailor as part of their horrible potion, although their powers don’t extend to actually being able to destroy life:

“Though his bark cannot be lost, Yet it shall be tempest-tost.”

Interestingly, apart from the poor shipwrecked sailor who presumably had to die in order to give up his thumb, Shakespeare’s tempests virtually never seem to end in death. In fact, of the 74 scripted deaths that actual occur on stage, not one of them appears to have been as a result of a storm at sea https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/72787/pie-chart-takes-tally-all-deaths-shakespeares-plays. In a world where sea travel was both crucial to Britain’s expanding empire, and perilous to the extreme, it’s amazing that these journeys most frequently end in rescue. It’s as if, like Macbeth’s witches, Shakespeare can conjure the storm but not cause actual fatality. Or, perhaps it’s just an interesting narrative device….

[Sidebar: Hamlet is one exception I can think of to the idea that all sea voyages in Shakespeare involve storms (maybe there are others I haven’t come across). His short sea voyage to England encounters pirates not tempests, but the journey is indeed one that is supposed to carry him to his death on the orders of his uncle. Hamlet sorts that out by putting his traitorous “friends” Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in his place.]

Enough of this. Of course, it’s The Tempest that takes the rich imagery of the storm at sea as the central motif of the play.

The plot

The play opens with a furious storm at sea, battering a ship and putting at peril the lives of all those on there. A young girl, Miranda, stands on the shore, witnessing the terrible tempest. But we quickly learn that this is just for show and the passengers have, instead, been transported safely to dry land – albeit to the dry land of a magical island ruled over by her father, Prospero, the usurped duke of Milan. Along with the two humans, two other beings live there: Caliban, a subhuman slave; and Ariel, a fairy-like creature. While they are in some ways opposites – body and spirit – in many ways they are kin, both in bondage to Prospero.

The ship-wrecked souls are Antonio – Prospero’s brother – and Alonso – King of Naples, his co-conspirator. Alonso’s brother Sebastian and a trusted counsellor Gonzalo make up one of the parties. But elsewhere on the island is Ferdinand, Alonso’s son and heir; and in a other spot Trinculo and Stephano – jester and butler, and the comic relief.

Through use of magic, mainly deployed via Ariel, Prospero controls events on the island. He brings Ferdinand and Miranda together so they can fall in love. He chases Trinculo, Stephano and Caliban away when they try to kill him and take over the island. And he confronts the equally treacherous Antonio and Sebastian (along with Alonso) with a harpy to terrify them because of their crimes. The play ends with the restoration of the right ruling line, the ship magically in one piece, and the spells lifted. Prospero eschews magic, also releasing Ariel from his bondage as promised.

The I of the storm?

The Tempest is the first play of the First Folio, but is thought to be one of the last plays Shakespeare wrote – in 1610 or 1611. One popular theory is that Prospero is a cypher for Shakespeare himself. Prospero puts aside his magic powers – evidenced through his staff and his book (his words and his pen) – and resigns himself to old age, passing the baton on to his daughter and her new husband.

It’s a dramatic image – quite literally – and a play as rich in symbolism as this one invites such interpretations. It’s really easy to expand this metaphor. Shakespeare/Prospero is part God/Author, part Ariel and part Caliban himself. As Prospero, he creates and controls worlds as well as words, but loses this power when his tools are gone. In releasing Ariel/the spirit, Prospero/Shakespeare is anticipating the end of not just his writing career, and his power over the spiritual, but his life. Equally, Caliban/the body’s slavery is evidenced through his adoption of language, which illustrates his subjectivity but – intriguingly – also gives him the words to curse his “masters”, as well as utter the most beautiful poetry:

“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises

Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again; and then in dreaming,

The clouds me thought would open, and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that when I waked

I cried to dream again.”

I’m sure I would just be hashing a thousand A-level essays if I were to explore this theme further! And the play has loads more packed into it, including its representation and exploration (if not outright critique) of colonialism. What’s interesting to me is that, despite its obvious allegorical themes, the characters still feel fully-realised rather than two-dimensional “types”, with multiple interpretations still possible and to be explored.

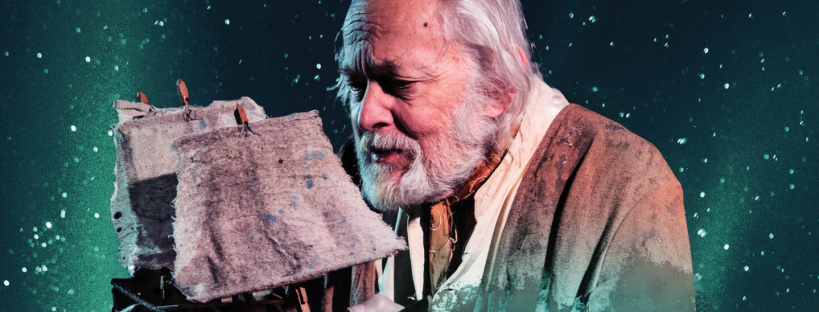

The production I saw was in the spectacularly tiny (in theatre-speak: intimate) Jermyn Street Theatre just a stone’s throw from Picaidlly Circus. You almost felt on top of the actors, and you even had to walk across the stage to get to the toilets! Michael Pennington played Prospero very convincingly, despite using a script throughout, something I’ve never seen before but generally didn’t cause too many issues other than a lack of eye contact. Initially I thought this was riffing on the idea that Prospero is controlling/narrating all the events of the play – a clever device – but, no, it did seem that he genuinely needed a prompt with the words.

I can definitely picture seeing this one again. But next play is booked: bring on Antony and Cleopatra.

[Update: I didn’t get to see Antony and Cleopatra because – weirdly – it was cancelled due to a terrible storm hitting the UK. The tempest strikes again, eh?!]